SHARE ヘルツォーグ&ド・ムーロンの設計で完成した、スイス・バーゼルの、1939年に建てられたコンサートホールの改修「Stadtcasino Basel」

ヘルツォーグ&ド・ムーロンの設計で完成した、スイス・バーゼルの、1939年に建てられたコンサートホールの改修「Stadtcasino Basel」です。施設の公式サイトはこちら。過去に同建築の建替えコンペが行われザハ・ハディドが設計者に選出されましたが、2007年に投票によってその計画が中止になったという経緯があります。その後、2013年にヘルツォーグ&ド・ムーロンに同施設の研究依頼がなされ、4年間の改修期間を経て完成したとの事。

The Extension

We explored a number of possibilities and variations for generating more space to house the additional facilities required for the Musiksaal. We focused on the area between the Musiksaal and the Barfüsserkirche, where the cloisters had been built in the Middle Ages. The area had consequently been cleared for architectural modifications by the Department of Historic Preservation. Initially we proposed extensions to the building between the Barfüsserkirche and the Musiksaal in analogy to the former cloisters but soon jettisoned the idea on urban, architectural, and operational grounds. The Stehlin Musiksaal was brilliantly conceived as a palazzo and all attempts to add on to the building looked like ridiculous patchwork. Similar to the annex of 1939, the extension facing the church would have been perceived as being behind the building and thus inferior to the façade facing Steinenberg.The only viable solution was to treat the Musiksaal as an autonomous building, uncoupled from the 1939 Casino.

以下の写真はクリックで拡大します

以下、建築家によるテキストです。

The Rise of the Cultural Mile in the 19th Century and its Urban Demise in the 20th Century

In the course of the 19th century, the town fortifications and the adjoining buildings of the former Barfüsser and St. Magdalen Convents were demolished, making room for what we would nowadays call a Cultural Mile along the southern fringe of Basel’s Old Town. These developments reflect the urban and architectural vision of those times.

The Casino (1826) and the Blömlein Theater (1831), based on plans by Melchior Berri, were followed in the second half of the 19th century by several important buildings designed in the neo-Baroque style by Johann Jakob Stehlin. Situated between Barfüsserplatz and St. Alban-Graben, they included the Kunsthalle (1872), the Stadttheater (1875), the Musiksaal (1876), the Steinenschulhaus (1877), and the Skulpturenhalle (1887).

In 1939, the old casino was demolished to make way for a new one, designed by architects Kehlstadt & Brodtbeck, and when the old Stadttheater was torn down in 1975, the resulting gap created a plaza for the new Theater, thus definitively heralding the end of the former Cultural Mile. Of the original buildings, only the Kunsthalle, the Skulpturenhalle, and the Musiksaal have survived.

Project of 2007, Defeated in a Plebiscite

A new building project designed to replace the 1939 Casino was defeated in a plebiscite of 2007. The project by Zaha Hadid had won first prize in an architectural competition but was rejected by the people, primarily because of its heavy massing. A few years later, in 2012, we were commissioned to conduct an urban study to determine how the limited and qualitatively inadequate space could be reorganized to accommodate ancillary facilities for the historical Musiksaal of 1876. The first phase of these efforts focused on the Musiksaal, one of the oldest, most important concert halls in Europe. It is the resident concert hall of the Basel Symphony Orchestra and also hosts concerts by the renowned Basel Chamber Orchestra and Basel Sinfonietta. With seating for 1400 people, it is internationally acclaimed for its exceptional acoustics. When the hall was built in 1876, service facilities were severely curtailed due to budget constraints. This issue was partially resolved in 1939 by tacking extensions onto the structure. Given these profound changes over the past 80 years, it is impossible for the outdated, cramped facilities to meet the needs of a contemporary concert hall. The survival of this invaluable venue for music necessitated urgent structural renovation and repairs as well as indispensable expansion to accommodate a spacious lobby, backstage facilities for performers, and other technical services.

The Extension

We explored a number of possibilities and variations for generating more space to house the additional facilities required for the Musiksaal. We focused on the area between the Musiksaal and the Barfüsserkirche, where the cloisters had been built in the Middle Ages. The area had consequently been cleared for architectural modifications by the Department of Historic Preservation. Initially we proposed extensions to the building between the Barfüsserkirche and the Musiksaal in analogy to the former cloisters but soon jettisoned the idea on urban, architectural, and operational grounds. The Stehlin Musiksaal was brilliantly conceived as a palazzo and all attempts to add on to the building looked like ridiculous patchwork. Similar to the annex of 1939, the extension facing the church would have been perceived as being behind the building and thus inferior to the façade facing Steinenberg.

The only viable solution was to treat the Musiksaal as an autonomous building, uncoupled from the 1939 Casino.

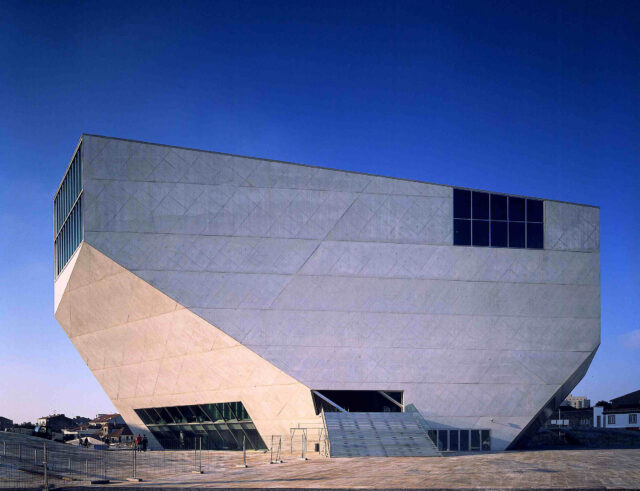

A Palazzo

As an independent building, the Musiksaal obviously had to be bigger than the existing core building of 1876. It would have to grow out of the old building as if it had always been there. That is why it was so important to design the addition, accommodating foyers, service facilities, rehearsal rooms and dressing rooms, so that it appears, at least at first sight, to be in the same neo-Baroque architectural tradition. Our design is based on the rear façade of Stehlin’s building, which had long been largely hidden behind the old extensions. With digital technologies we scanned the façade and we reconstructed it to original scale.

The solid masonry of the historical façade has given way to a façade of insulated, reinforced concrete with rear-ventilated cladding in keeping with contemporary building technology and climate control. We decided that wood would be the most suitable cladding and modified the geometry of the original façade just slightly to meet the structural requirements of that material.

When the Musiksaal was built in the 19th century, certain elements were made out of wood and then painted to match the design of the whole, like the seemingly massive cornice, which had been painted to look like the stone of the façade. The same applies to the columns inside, which had been constructed in wood or plaster because of the acoustics. They, too, were painted to look like stone.

The Lane

Separating the operations of the concert hall and the Stadtcasino also meant demolishing the former entrance area with its staircase. This allowed for a direct connection between Steinenberg and Barfüsserplatz, where carriages used to pull up, prior to the demolition of the Berri building in 1938 and the construction of the new Stadtcasino in 1939. Thus, the Musiksaal is now oriented both toward the former Steinenberg Cultural Mile and Barfüsserplatz; it is a clear-cut presence on Barfüsserplatz, sharing the space on equal footing with the imposing Barfüsserkirche. The area between the Church and the Musiksaal, once merely perceived as kind of rear courtyard, has become a new public space.

This volumetric recovery of urban space draws attention to other weaknesses. The 1939 Casino has always turned its back to the square, with a rear façade that looks like an apartment building. Furthermore, the 1980s design of Barfüsserplatz includes a tram stop that obstructs the square. The situation undoubtedly needs further consideration, especially as Barfüsserplatz is one of Basel’s most important public spaces.

The Stehlin Musiksaal

The Musiksaal has been significantly modified several times since it was built in 1876, first in 1905 in conjunction with the Hans Huber Hall built by Fritz Stehlin, at which time an organ was built into the hall, stucco decoration applied to the ceiling, the busts of musicians placed against the walls, and the color scheme revamped. The second major refurbishment followed in 1939, when the old Casino was torn down to make room for the current building by architects Kehlstadt & Brodtbeck. A significant increase in the incline of the rear balcony provided access from the balcony to the newly erected building in between. Further adjustments in the years that followed include closing off the skylight and the windows, replacing the historical seating, redesigning the historical chandeliers, replacing the original parquet, and introducing an entirely new color scheme.

The current restoration of the concert hall has been carried out in close collaboration with the Cantonal Department of Cultural Heritage. The aim of restoring the building to its original state at the time it was first renovated in 1905 went hand-in-hand with the top priority of preserving the hall’s acoustic properties. We opened up the skylight and the windows again, re-created the original seating, reduced the incline of the balcony, laid a duplicate of the original parquet flooring, and restored the color scheme of 1905.

The Foyers

The enlargement of the overall volume directly adjoining the concert hall generates space on several levels to accommodate foyers and bars as well as rehearsal rooms, dressing rooms and service facilities. The Hans Huber Saal will continue to host chamber music and is now accessed directly from the new foyers.

The new foyers flanking the concert hall are arranged on two levels, accessing the parquet and the balcony. We have exposed the façade facing the concert hall, mirroring it as a new outside wall. For the end walls, however, we use mirrors, a popular element of the 19th-century, making the hall more spacious in combination with the mirrored ceiling. The corners of the upper foyer are detached from the side walls, so that it seems to be a floating, elliptical panel. The two levels of the foyer, with a central hole, are thus perceived as a single space.

Outside, we focused on simulation in designing the extension of the Stadtcasino, while inside we celebrated the stylistic elements of the 19th-century by heightening the artificiality of form, material, and color.

The Staircases

Despite the urban constraints on the extension of the Stadtcasino, we wanted to provide as much space as possible for audiences. Therefore, in addition to the foyers, we added loggia-like recesses to the expansive staircases, where people can linger during intermissions.

We had the original brocade wallpaper reproduced by the Manufacture Prelle in Lyon. Founded in 1752, the company had already woven these wallpapers for the Opéra Garnier the year before the concert hall opened in 1876.

We worked out a custom-made design for the new parquet of the Casino. The lens-shaped geometry of the pattern echoes the wallpaper, while the parquetry is laid out left and right, following the grain of the wood in reference to the historical herringbone parquet of the concert hall.

Taking inspiration from the historical crystal chandeliers, we designed the “Parrucca” luminaire—modern LED lighting to line the staircases in the casino. The play of the light is multiplied by the silver of the hammered metal on the ceilings, which artificially heightens the room.

The Hans Huber Saal, the Rehearsal Rooms and the Dressing Rooms

Fritz Stehlin built the Hans Huber Saal for chamber music in 1905 to complement the concert hall. It has been largely restored to its original state in cooperation with the Department of Cultural Heritage. The musicians’ foyer and the dressing rooms built along with the chamber music hall have been similarly restored. In addition to returning to the original color scheme, we referred to historical documents in order to reconstruct the paneling, windows, and doors that had been replaced in later renovations.

The existing dressing rooms of the Hans Huber Saal have been supplemented by new rooms on the top floor of the extension for the casino society. There are also three dormer windows that afford new views of Barfüsserplatz and the Barfüsserkirche and, on the other side, of the historical roof of the concert hall, thanks to the newly created courtyard.

(Herzog & de Meuron, 2020)